The following was published in Soundboard Magazine, the Church of Ireland Dublin Diocesan Music magazine. The publication at the time contains many 'typos' - here is a corrected version.

Organ Tuning

"Just read your article on organ tuning. It certainly explains the demands and intricacies of the job very well." Stephen Alliss, tuner for Harrison & Harrison.

Much of our work is spent on major work such as sorting out whole organs (action, wind system, damaged pipes etc.) or saving redundant organs and finding new homes for them. However, the main reason for our regular contact with organists is for routine tuning and / or maintenance.

This article consists of a short list of considerations with regard to tuning, which may be of interest. The intention is to highlight the various problems which we face in this respect.

Pitch

Well, more often than not our hands are tied, as the approximate pitch of an organ has been chosen upon the commissioning of the organ. Typical organs in our churches (Conachers, Telfords etc.) are the guts of a semi-tone sharp, and it’s difficult to pull this down to A440 (we did so at Whitechurch and we are aware of the problems!). It is then a consideration for organists to transpose down music that involves congregational singing if this is within their ability. (This is aside from the older hymnbook which sets most tunes for SATB with the top line being too high for the average congregation.)

Quite often it is necessary to reset a pitch of one division to lessen the flattening effect of dust and dirt. And often we find ourselves tuning a division deliberately flat or sharp to another division in order to cater for temperature swings. Both of these areas differ depending on whether a division is enclosed (i.e., in a Swell or Choir box) or exposed (as would be the norm for the Great and Pedal).

Temperament

Temperament need not concern most organists, nor do they have to understand it. Temperament is basically the relationship of one note to each of the others within the 12-note scale. A good example (if extreme) might be Arabic music, or more locally, bagpipes, both of which use a temperament much removed from ours. Semitones end up very wide (i.e., the distance between some of them can end up being half way between a semitone and a tone). We sometimes discreetly twist the temperament of an organ to favour the more common keys (i.e., the more sharps or flats the prevailing key signature contains, the less sweet the tuning becomes). We have successfully produced very pleasing temperaments in Christ Church Cathedral (by request), and in our recently-completed project at the Church of the Assumption, Milltown.

You might well say “let’s not mess about with this business at all”. Well, most organs are tuned to “equal temperament” which Is a temperament in itself. The problem is that there are 12 notes in the scale, and using an analogy, we nominally give each semi-tone a value of 100 cents. A scale therefore equates to 1200 cents and a pure (major) third to 386 cents. So if we take pure thirds, e.g., C to E, then E to G#, and G# to C and add up their total in cents we get 3 x 386 = 1158, noticeably less than an octave. See the problem?

So it may be seen that some form of tempering is needed in order to keep the octaves in tune. The good thing about equal temperament is that all keys are usable — the bad thing is that not one key is really pleasing. Whatever one chooses, compromises are the order of the day, unless one provides a double of some notes to lessen the problem (which has been done, but no examples in Ireland though).

Basic tuning (temperament) is usually set in the middle octave of the Great Principal (as it is central in pitch (and often in geographical placing too) to the rest of the organ. Thereafter it is copied throughout the organ via octaves for speed. This creates a problem for us, as tuning in octaves allows for a wider swing of “out-of- tuneness” before a beat arises, especially in the bass. Tuning in thirds, fourths and fifths is more accurate, but time never allows. Diapasons, principals and mixtures aren’t too bad, but when it comes to copying across to the other families (flutes, strings and reeds) the trouble starts. Most difficult perhaps are Rohr Flutes and Stopped Flutes, which have less assertive harmonic content. Quite often one has to listen for the twelfth or the seventeenth to tune these. Try that with a head cold!

Temperature

When the temperature rises, everything goes sharp (sometimes to an alarming degree). However, the reeds are the least affected here and so it can appear that it is the reeds that need tuning. In reality that is often what we do — yes, but only because they constitute the smaller percentage of the whole. This is a big problem where say, heating comes on on a Sunday morning and the organ has six hours warming effect. What usually happens is that all exposed pipes heat up and sharpen, whereas those in the Swell box don’t change.

The preceding point of course has a bearing on humidity levels where inside temperature is kept stable and the outside temperature drops. Effectively the heating is turned up. We look after several organs where this is a problem. Low humidity causes timber pipes to shrink, creating at least a variation in regulation (and consequently tuning), or worse. Actions too are sensitive to humidity levels. It’s not unlike a door at your home, which jams in damp weather.

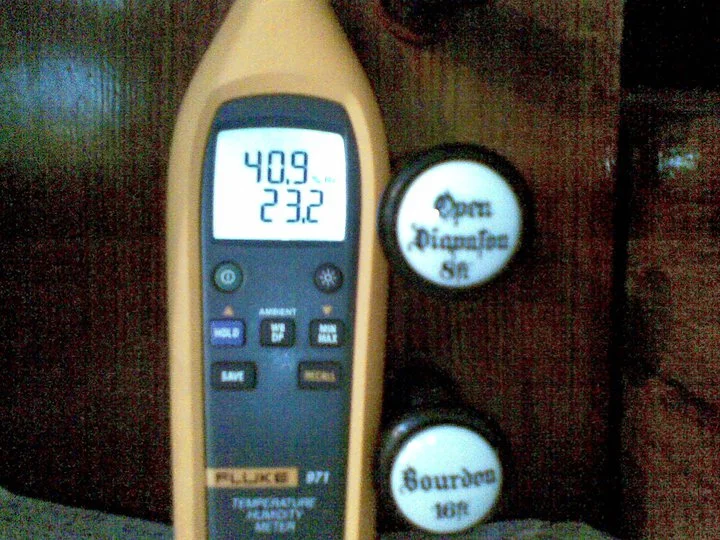

Below we see a temperature of 23.2 deg C, with a resulting humidity reading of 40.9% when it was below freezing outside. I've seen these sorts of readings quite often in a gallery situation, where the heat rises and stratifies. But this particular church......the organ is at ground level......so yes.....23.2 degrees was what the church was kept at. Any organ will balk at such extreme conditions: it is generally accepted that anything lower than 55% RH is damaging. This organ ended up with splits along the length of its bellows. Thankfully the soundboards recovered from the hit with time.

Access

Most organs are tightly laid out (and difierently laid out too). Our Milltown organ can only be accessed from the front (see photo immediately below). So to get at the back stop of the organ (the Swell Open Diapason) one has to get through the front pipes, four stops of the Great, the Swell shutters and the five stops of the Swell which are in front. No fun! Even where access is reasonable, the act of tuning requires one to be in a staid position for some time, usually on ones knees, or crouched or balanced somewhere. It is usually very stressful on the lower back and knees.

Drawing

This is the effect when two pipes “fight” with one another. This is one of the reasons we usually avoid placing semitones next to one another. This can happen sometimes when one of the pipes isn’t even sounding! Another reason for drawing would be a less-than- satisfactory supply of air owing to action deficiencies (either inherent in the organ or due to action failures). Stop action and soundboard problems can equally apply here too.

Wind delivery

Quite often there can be a “shake” in the wind pressure on attack, which will give the sensation of things being out of tune. (Fitting a mini-bellows, called a concussion bellows, at the soundboard(s) can often reduce this.) Also, instability can sometimes be traced back to an erratic blower.

Inevitably, compromises must be made where wind delivery to the pipe(s) is poor or variable. Reasons might be that the pallet feeding same is too small or borderline (this might not be noticed until one adds more stops), or a conveyance feeding the pipe has been damaged, or is simply too small in diameter, or where a pipe serves two purposes (e.g. the bottom octave of a flute and string are often common, so the same pipe receives air from two different sources).

Faults within the pipes themselves There can be many problems here: wooden pipes can split or the stoppers may not fit well, dust and dirt can put flues off-speech, pipes can often collapse on themselves, a reed can be silenced with a speck of dirt, bad/unstable voicing (very difficult when it comes to mixtures and reeds). Shown in the photograph (above) are the main types of pipe. From top to bottom are a stopped pipe, the tongue and shallot of a reed, a pipe with slot tuning and one with slide tuning. Basically, the vibrating length is adjusted in all cases. Another type of tuning is cone tuning, where the substance of the pipe Itself is tapered in at the very top. It’s a very good form of tuning, but misunderstood by less-competent tuners, which can lead to much damage (and there are many examples of this).

Background noise

Very often a problem in cities — people talking, traffic, vacuum cleaners, etc.

Sheer quantity

One might associate getting the organ tuned as being in the same category as a piano. Don’t forget though, 10 stops each with 56 notes equals 560 pipes! And it only takes one out of tune in the correct place to mess the whole thing up!

The sound of a pipe organ is constant, whereas all other instruments are intermittent and the sound immediately starts to decay. This can be bad for the pipe organ user as It only takes one note slightly out of tune for the whole organ to sound badly, and since sometimes notes are sustained, well..........

Shading

This is another really big problem. The presence of even the tuner’s arm or body can affect the environment such that when same is removed, pitch alters. This is especially noticeable in close ciicumstances such as in a Swell box. On small organs, where opening a panel is necessary to access the pipes, one often has to guess at a tuning point, return the panel to its position and listen - repeat as often as is required - a situation that requires much patience. A common complaint we receive is that the Celeste is out of tune. Many people (including some tuners believe it or not!) do not realise that the Celeste is deliberately tuned out of tune with the Salicional or Dulciana on the same division. It produces an undulating effect, which, if pipes are properly on speech, is gorgeous. The Vox Celeste is usually tuned sharp, but at Milltown we opted to go flat (as would be the norm with an Unda Maris); it’s more relaxing. We really need to sit back and realise really how beautiful some of these lovely old string stops are. The strings at Milltown really are very pretty now.

Next time you ask for your organ to be tuned, the above may help in appreciating what can be involved, and we will always deal with specific complaints on a prioritised basis. But to be absolute, it could take weeks not hours — something your treasurer may not appreciate!